|

My primary objective as a composer is to write beautiful and stimulating music. For me, “beauty” is embodied by temporal and in particular, timbral attributes. Over the past ten years, I have worked towards a compositional model in which the “color” and “texture” of available sounds are derived from multidimensional models of timbre spaces.

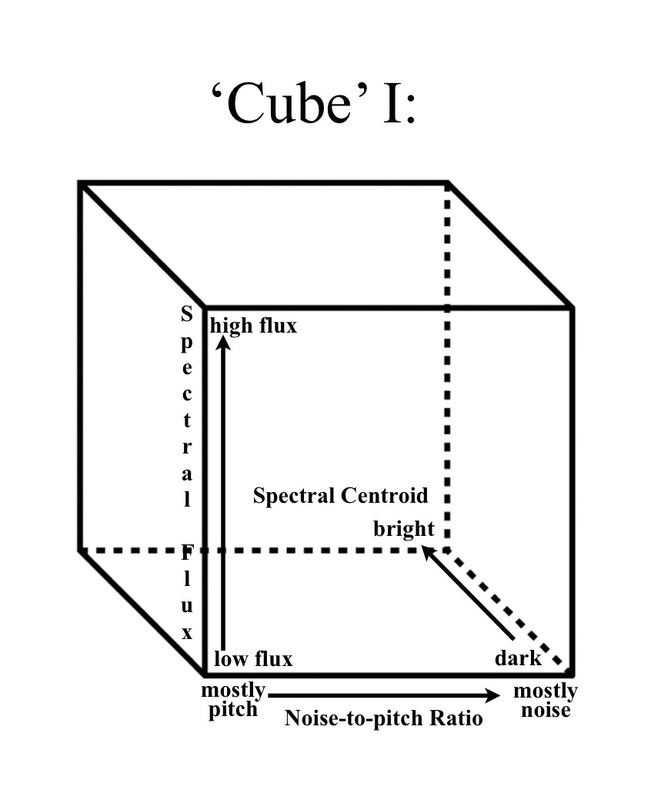

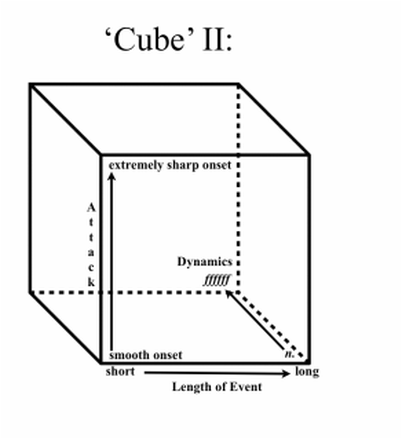

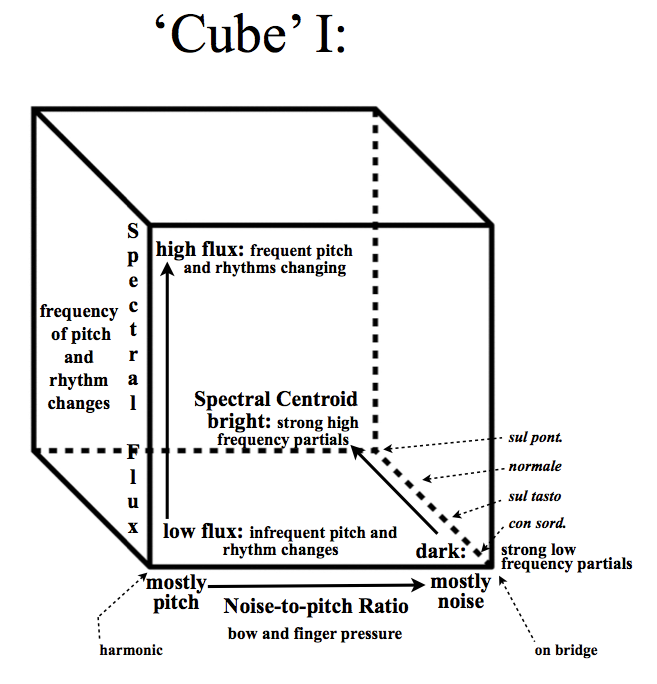

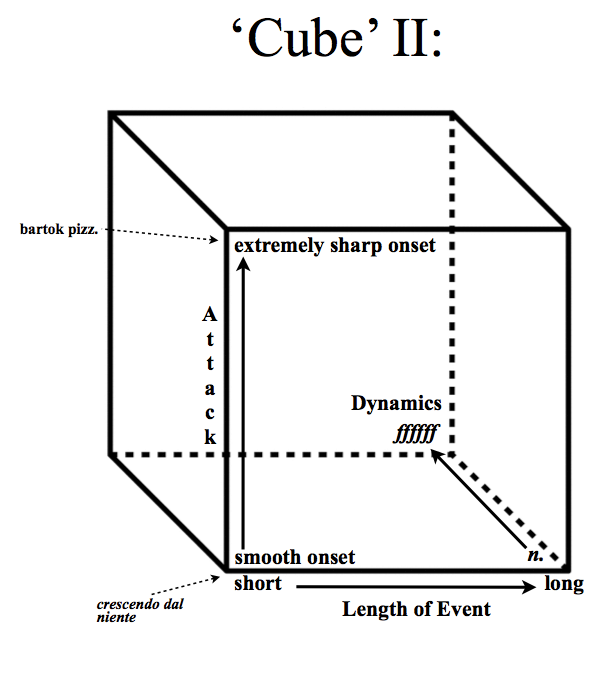

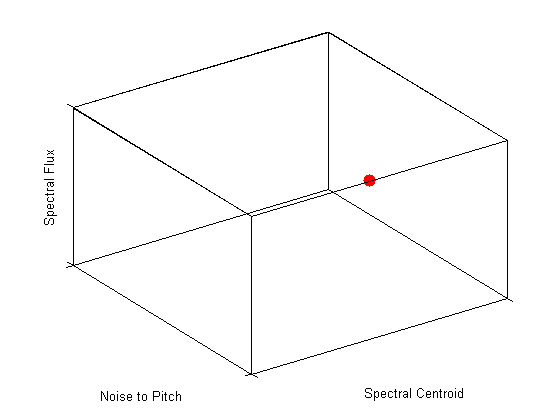

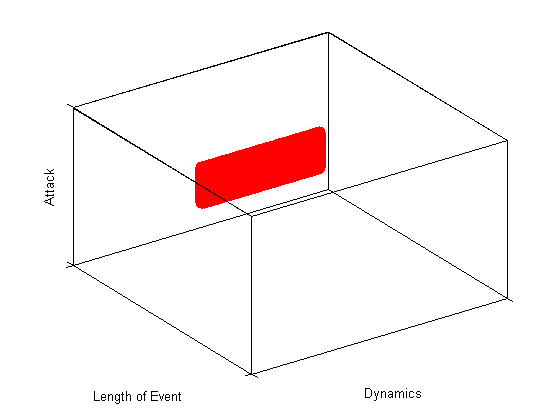

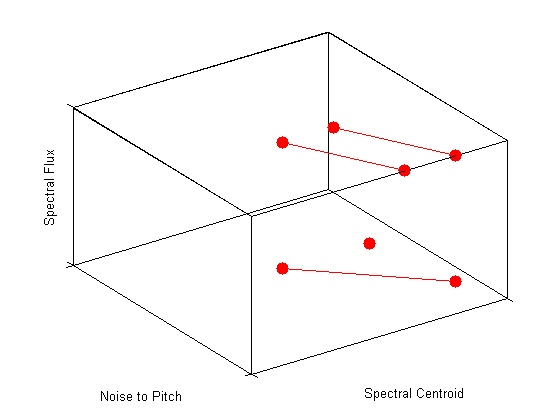

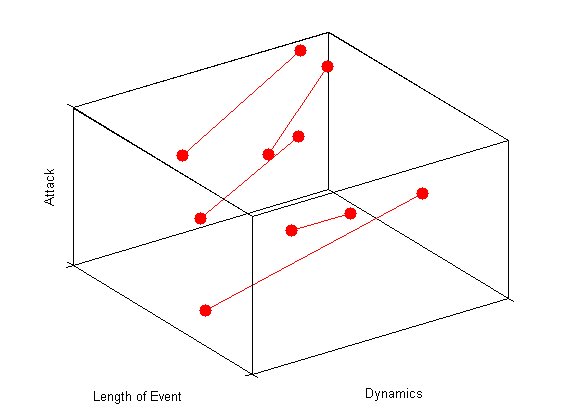

The problem with timbre is that it is ill-defined. Unlike pitch and loudness, there is no simple, objective, or single dimensional scale that describes this phenomenon. Timbre can however be described as a multidimensional attribute of sound and “continuous perceptual dimensions correlate with acoustic parameters corresponding to spectral, temporal, and spectrotemporal properties of sound events.”[1] As timbre became increasingly central in my composition, I adopted a hybrid model that integrates both the “color” and “texture” of sound, and incorporates both static and dynamic attributes of timbre. The “color” of sound is described in terms of an “instantaneous snapshot of the spectral envelope,” while the “texture” of a sound describes the “the sequential changes in color with an arbitrary time scale.”[2] This view of timbre was developed at Stanford University’s CCRMA by Hiroko Terasawa and Jonathan Berger, and hints at two important compositional elements in a piece: 1) static, vertical pitch and chordal structures, and 2) dynamic, horizontal temporal processes. While these elements are important, this definition is still rather vague as to the descriptive factors of timbre. While I have been attracted to other composers’ and researchers’ timbre models (including models by Pollard & Janson, Grey, McAdams et al., Wessel, Penderecki, Spahlinger, Saariaho, Grisey, Slawson, Lerdahl, Cogan, and Erickson, to name just a few), I have sought a model for my own purposes that is less limited and open to deeper dimensionality. The goal for creating my own compositional timbre model was to find a way to allow the perceptual properties of timbre to address and control any aspect of a composition across multiple dimensions. For the purposes of my own works, I propose a set of two interlocking spaces or “cubes” as I like to visualize them. The first cube essentially controls the frequency components of the sound. This compositional timbre space has the following three dimensions: spectral flux, spectral centroid, and noise-to-pitch ratio. The first dimension, spectral flux, measures the Euclidean distance between two spectra, or rather, the change of spectral energy over time. By extension, this dimension can be used to control rhythms or the frequency of pitch changes. This analogy provides a measure of density in time analogous to spectral flux at the intra-event level. For example, in my model, a sound with high flux means that there is a high rhythmic activity, or that pitches are changing quickly, while a sound with low flux would be one in which there is either a low rhythmic activity, or the pitches are stagnant. The second dimension controls the noise-to-pitch ratio and is similar to Saariaho’s “timbral axis.” On one end of the axis there are sounds that are mostly “pure” pitch—that is, sounds that are close to sine waves. By contrast, the other end of the axis is “mostly noise.”[3] The third dimension controls the spectral centroid, or rather, the average centroid over time, and controls the brightness and darkness of the sound. For example, if the space was evaluating the spectral centroid for a violin sound, this axis would have four reference points--con sordino, sul tasto, normale, and sul ponticello—plus every shifting possibility in between. Cube I however, is missing key information, namely: the quality of the attack, the dynamic level, and the length of the event entering into the space. To solve this dilemma, I use a secondary cube to inform these decisions. This second cube works in conjunction with cube I. The first dimension—attack—controls how the sound or gesture’s articulations are treated, ranging from no attack (or a smooth onset) to a sharp attack (sharp onset); the second dimension controls the length of the event, sound, or gesture that enters into the timbre cube; and the third dimension controls the dynamics. Virtually any aspect of a composition can be viewed and decisions can be made based on these two combined cubes. What is interesting about this model is that the function of each dimension changes depending on the source material inserted into it and the function of the desired result. For example, I could either place a sound into the space to learn more about its timbral characteristics, or I could map the instrumentation/every sound I wish to use in the piece onto the space’s dimensions and “see” the possible coordinates. Using this model, timbre itself controls and informs the composition. It can be used to derive rhythms, generate a form, harmony, rate of material, or simply inform the orchestration of the piece. With this model, one can work with any sound, or instrumentation. While this is process is more intuitive than scientific, it abstracts the original sound and allows one to base a piece’s timbral decisions after an already existing acoustic model. In my most recent works I have used nature sounds as stimuli and “everyday” sounds as material for my compositions. I am fascinated by the “color” of sounds and timing of events that surround us in our everyday lives. They are filled with rich material and offer incredible musical possibilities. With my model, one can insert material into the space and zoom in and out of it as one desires. Similar to painting, with this model the composer not only gets to choose the “landscape,” the composer can also control the perception and magnification of the material. The dimensions change slightly depending on what one chooses to highlight. Similar to visual art, the resulting piece is not a mere copy of the source, but rather an abstracted representation of the original. At the University of Virginia, I continued my timbre research, working with graduate students, composing new works, and writing articles. Emergent in my recent works is a common theme and exploration of “timbre space” and “timbre in space.” Recent/current projects include a series of works exploring timbre, text, and the voice; multiple collaborations with dancers and multichannel audio/live-processing, a work for found percussion and live-electronics, and an installation combining paintings with immersive sound-scape compositions. My most recent pieces illustrate a trajectory through which composing with timbre yielded new creative insights and compositional techniques. With this model, each composition serves as a piece of a puzzle whose image reveals a more clear and complete understanding of timbre. [1] McAdams, S., Giordano, B., Susini, P., Peeters, G., & Rioux, V. (2006). A meta-analysis of acoustic correlates of timbre dimensions [Lecture slides]. Retrieved from McGill University: http://www.dafx.ca/slides/keynote3.pdf "[2] Rossing, T.D. (2012). Pitch and Timbre. Lecture conducted from Stanford University, CA. [3] Saariaho, K. (1987). Timbre and harmony: Interpolations of timbral structures. Contemporary Music Review, 2(1), 93–133. Reid's DMA Final Project:

|

Reid's Compositional

|